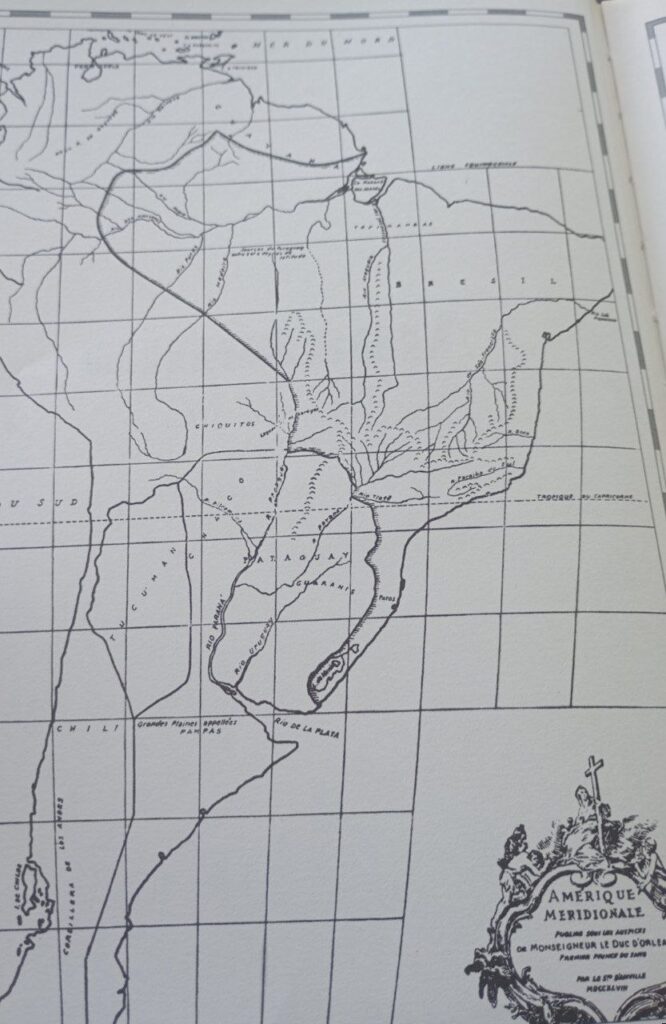

Looking at the map of South America, it is easy to see that the natural north-south integration axis of the subcontinent is formed by the Orinoco, Negro, Amazon, Madeira, Guaporé, Paraguay, Paraná, and Plata rivers, which fit between the Andes and the Cerrado, extending for approximately 10,000 km and interrupted by only one “dry point” between the Amazon basin and the Paraguay-Paraná-Plata basin.

The strategic importance of this integration corridor for the South American interior, termed the “Great Waterway” by engineer and professor Vasco de Azevedo Neto, had already been recognized at the end of the 18th century by the governor of the province of Mato Grosso, Captain-General Luís Albuquerque de Melo e Cáceres, and in the early 19th century by the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt.

In June 1992, the governments of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay signed the agreement on fluvial transport along the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway at a meeting held in Las Leñas, Argentina, establishing plans to guarantee navigation with a draft of six feet (1.80 m) over a 3,442-kilometer stretch between Cáceres (MT) and Nueva Palmira (Uruguay).

Immediately, the international environmentalist apparatus began mobilizing to block the project!In early 1993, the U.S. NGO “Wetlands for the Americas” published a report titled “Initial Environmental Analysis of the Paraná-Paraguay Waterway,” funded by the “W. Alton Jones Foundation”—an NGO linked to the oil magnate and chairman of the Cities Service Company—that highlighted the “vulnerability” of the Pantanal (a vast wetland and floodplain region) in Mato Grosso as the main obstacle to the project.

From that point on, the international environmental apparatus began spreading the idea of the Pantanal’s “untouchability,” elevating it to the status of an “ecological sanctuary” that, according to some alarmist assessments, could even “dry up” without the precious support of traditional funding sources…

Starting in 1994, the WWF sponsored a series of photographic exhibitions in Brazil and abroad, leading to the creation of the NGO “Living Rivers” together with other international NGOs specifically tasked with preventing the waterway’s implementation.

Among its members were the “American International Rivers Network,” the “Environmental Defense Fund,” the Dutch “Both Ends,” “Ação Ecológica (ECOA),” “Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV),” “Ecotrópica” in Cuiabá (MT), and “CEBRAC” in Brasília (DF).In the mid-2000s, the Mato Grosso state government and the companies “American Company of River Transport (ACBL)” and “Inter-American Navigation and Commerce Company (CINCO)” signed an agreement to build a multimodal river-rail port terminal in Morrinhos, 85 km from Cáceres, representing a US$12 million investment.

The environmental licensing process for the project then began, but on January 3, 2001, Judge Tourinho Neto, president of the 1st Region of the Federal Regional Court (TRF) in Brasília, partially upheld an injunction granted on December 19 by Judge J. Sebastião da Silva of the 3rd Federal Court of Mato Grosso, requiring IBAMA to issue a single environmental license for the entire Brazilian section of the waterway (MT and MS).

The injunction stemmed from a public civil action filed by Mato Grosso’s state Attorney General Pedro Taques, together with prosecutors Gerson Barbosa and Fania Helena Amorim, requesting the cancellation of all existing environmental authorization processes for the waterway and the preparation of a single environmental impact study covering all works within the waterway’s scope, including dredging, maintenance, and construction of access roads to ports and terminals.

Since then, due to federal court injunctions, an absurd legal impasse has persisted over the Brazilian section of the waterway, imposing an embargo on the installation of new ports or the expansion of existing ones, as well as on works providing access to terminals.

Consequently, at the end of 2004, the governments of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul decided to take legal action to appeal the judicial decision blocking full implementation and use of the waterway, focusing on two aspects:

- Legal, environmental, and technical issues;

- Administrative measures, such as sending a request to state governments and navigation companies to immediately lift the restrictions imposed on navigation.

By a highly suspicious coincidence, one month after the states’ initiative, the U.S. NGO “The Nature Conservancy (TNC)” announced a US$2.5 million program for the conservation of the Paraguay and Paraná basins, including the Pantanal region.

Despite some localized benefits, the program’s undeclared objective is to make the waterway’s implementation up to Cáceres (MT) unfeasible due to an alleged incompatibility with river and Pantanal conservation.

The geopolitical interests of the Anglo-American establishment are barely concealed in the program’s justification, as stated by The Nature Conservancy’s representative in Brazil, Ana Cristina Ramos: “The main threat to the Pantanal is the expansion of agriculture and cattle ranching, and the destruction of riparian forests in the Cerrado.”

She also claims that, in her view, agriculture was one of the factors that nearly destroyed the Mississippi forest. Eight decades ago, that region of the United States was at a stage of development similar to Brazil’s Center-West, and large-scale use of rivers for energy production and agriculture dried out the wetlands. “The changes that have already occurred in the Mississippi basin are frightening, and we want to prevent the Pantanal from suffering the same fate,” emphasizes João Campari, the NGO’s director.

This essentially means that, according to this view, in the name of hypothetical environmental impacts, the area influenced by the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway cannot achieve development comparable to that provided by the extraordinary Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio waterway system—without which there would be no famous American “Green Belt,” and without which, in turn, the United States would not be the world’s largest agricultural producer!

On March 4, 2005, the Mato Grosso government organized a major international seminar on multimodal infrastructure in Cuiabá, where the waterway was one of the main topics discussed.

The seminar’s host, Governor Blairo Maggi, made it clear that cooperation would be needed between the government, the public prosecutor’s office, and the judiciary to find a way out of the technical-legal impasse blocking the waterway’s full development.

The strategic importance of river transport for Mato Grosso was explained by State Secretary for Infrastructure Luiz Antonio Pagot in an interview published in April 2005 by Tecnologística magazine:

“Mato Grosso is the state of waters.

If the law allows us to turn our waterways into navigable routes, we will decisively contribute to the region’s development and to reducing the transport costs of our products.

This mainly means lowering food costs and generating jobs and income in shipbuilding.”

Pagot described the hydrological complexes formed by the Mortes-Araguaia, Teles Pires-Tapajós, and Guaporé rivers, whose navigation could be fully enabled with the implementation of certain hydroelectric projects and locks.

Regarding the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway, he was categorical: “In some stretches, one could say there is a beginning of hydrological infrastructure, but it is still far from being like the Canadian, American, or European ones.”

Therefore, it is necessary to clear channels, rebuild low and narrow bridges, and stabilize banks to prevent river siltation.

And he emphasized: “As if all that were not enough, we have the total ignorance of paid prosecutors or international pseudo-ecologists who do not even know what a wave is and the good it does for banks by preventing erosion.

But we see reports from these authorities that are pure absurdity.

No one wants to bypass environmental laws, but we want to be independent.

Let decisions about waterways be Brazilian and not influenced by organizations that defend jobs in the Northern Hemisphere!

Waterways are not a problem, but a solution for Brazil.”

In the same magazine, Michel Chaim of “Cinco & Bacia,” one of the region’s largest navigation operators, criticized excessive bureaucracy and undefined government actions that make waterway development unfeasible and strongly condemned the international ecological apparatus:

“We have always known about environmental terrorism!

We suffer from the actions of environmental prosecutors who, in collusion with foreign environmental NGOs, impose a demonic pact to prevent Brazil’s development.”

Michel Chaim stresses that environmental responsibility is unquestionable and must be observed, but he asserts:

“However, as a citizen and as a Brazilian company that generates jobs and pays taxes, we cannot accept the use of environmental issues as a livelihood for thousands of NGOs!

They are funded by foreign capital with fantastic and irrational claims that cannot withstand the slightest technical argument.

Against these enemies of Brazil, we are and will remain fierce adversaries.”

He remains optimistic about the future of river transport in the country and estimates that, in the long term, if a fluvial route is interconnected with the Madeira and Jauru rivers in the Amazon basin, it will be possible to establish a 10,000-kilometer multimodal system from Buenos Aires to Iquitos, Peru.

This is a vision of integration for the South American interior that troubles those deceived by the discourse of the “international environmental mafia” and disturbs many minds among the most powerful in the Northern Hemisphere!