“Everything that exists in the periodic table exists in the Amazon.”

— A statement overheard from a geologist with extensive professional experience in the region

“Even with the massacre of 29 prospectors at the beginning of the month and the siege by the Army, adventurers remain in the vicinity of the Roosevelt Reserve hoping one day to return to prospecting, with or without the permission of the Cinta Larga.

The risk to life comes at a price: the potential of the diamond mines in the reserve is one million carats per year, equivalent to US$500 million, according to unofficial calculations by technicians from the National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM), of the Ministry of Mines and Energy.

Roosevelt Reserve diamonds are of above-average quality. They can be sold at high prices, says Deolindo de Carvalho, head of DNPM in Rondônia.

According to the Rondônia Prospectors Union, approximately US$8 billion in diamonds have already been mined in the reserve and, so far, the seven alleged large mines in the area remain untouched.”

— O Globo, April 25, 2004

It is unlikely that all 118 elements of the periodic table are actually present in the Amazon; the experienced geologist’s phrase is more an expression of awe at the vastness of the natural resources hidden beneath the planet’s most promising mineral province.

Nearly half of the Amazon lies in the Precambrian shield, a geological era particularly rich in mineral deposits.

Nineteenth-century travelers and naturalists showed little interest in geology, focusing instead on the region’s fauna and flora.

The first systematic effort to map the region’s mineral resources was the Radam (Radar Amazonia) project, launched in 1970 by the military government.

Oil deposits in the Amazon extend from the coasts of Pará and Amapá to the Peruvian border.

The late former congressman and president of the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), Haroldo Lima, often expressed to me his frustration over Ibama’s veto of oil exploration on the Acre-Peru border.

More recently, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, Ibama, and NGOs combined forces to block an experimental well on the Amapá coast, 500 kilometers from the mouth of the Amazon River.

In 2017, President Michel Temer issued a decree opening part of the National Copper and Associates Reserve (RENCA), located between Amapá and Pará and rich in phosphate, copper, gold, titanium, zinc, tungsten, and tantalum.

Brazil imports more than half the phosphorus used in its agriculture; opening RENCA would have reduced that dependency.

An international campaign led by NGOs and Hollywood celebrities—highlighted by a tweet from Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bündchen—pressured the government into revoking the decree, leaving immense underground wealth untouched until NGO leaders deem otherwise.

The scandalous blocking of the potassium mine in Autazes, Amazonas, reveals how state institutions—the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Judiciary—cooperate to freeze Amazonian mineral resources.

Brazil imports 85% of the potassium used in its agriculture, costing billions of dollars and burdening the trade balance, yet Autazes could produce two to four million tons annually.

Since the mine was not on indigenous land, Ibama declined to conduct the environmental impact study, insisting it was the responsibility of Amazonas state’s environmental agency, which had already approved the project.

The Judiciary nonetheless ordered Ibama to perform the study, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office appealed the approval, citing proximity to indigenous land.

One prosecutor even stated that the only way to halt the project would be to expand the indigenous territory to encompass the mine site.

Adding to the outrage, an NGO began using the term “self-demarcated indigenous land”—meaning demarcated by the NGO itself, without Funai’s involvement or adherence to national legal standards.

The result: stalled investment and continued dependence on imported potassium for Brazilian agriculture.

The global rivalry between China and the United States has eroded confidence in the dollar as the international reserve currency and bolstered gold as a store of value coveted by central banks worldwide.

The Amazon contains promising gold provinces within indigenous lands and full-protection conservation units.

Most of this gold is extracted illegally, smuggled out of the Amazon and Brazil, causing serial losses: municipalities and states forego the Financial Contribution for Mineral Extraction (CFEM), and the federal government loses taxes evaded through smuggling.

Niobium—an essential mineral for aerospace, space, nuclear, and high-performance alloy industries—is abundant in the Amazon’s Cabeça do Cachorro region in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, near the Colombian border.

Access is prohibited, however, because the deposits lie within the fully protected Pico da Neblina National Park and indigenous lands closed to mining.

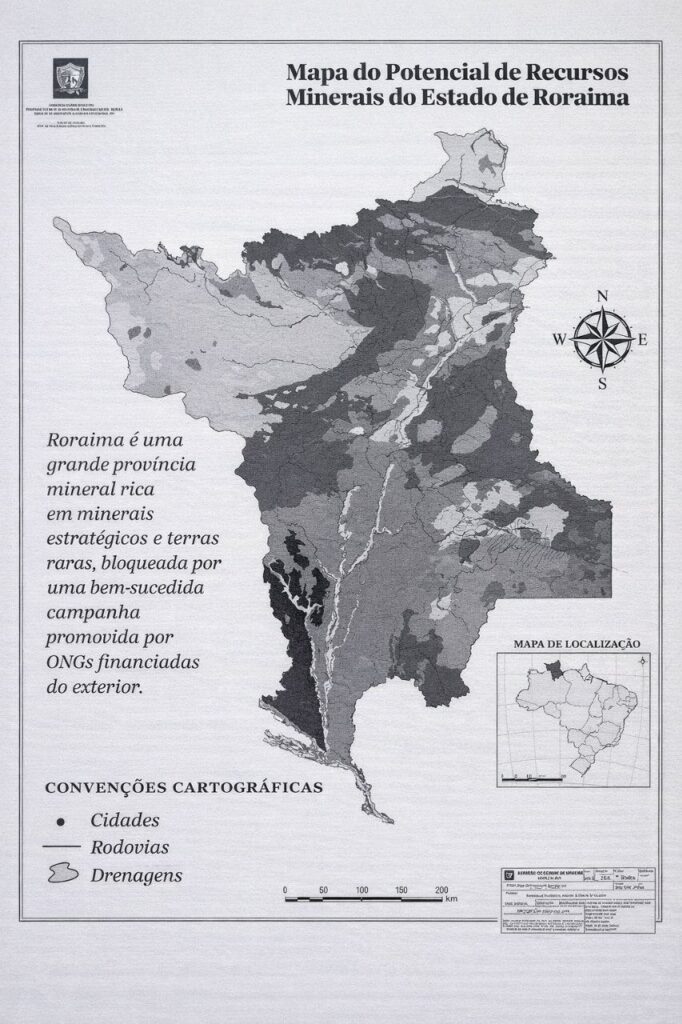

Roraima’s case is unique: 70% of the state’s territory is off-limits to mining, classified as indigenous land or conservation units.

Paradoxically, nature endowed Roraima with one of Brazil’s richest mineral provinces, yet its population cannot benefit from these resources.

The potential of the Amazon’s mineral frontier is best illustrated by the only state that partially broke the blockade by initiating large-scale mining in the 1970s, before NGOs and state agencies fully coordinated their opposition: Pará.

In 2021, Pará’s mineral trade surplus reached US$49 billion—compared to Brazil’s national trade surplus of US$61 billion—and the state accounted for 35% of the country’s mineral exports.

Just two municipalities, Parauapebas and Canaã dos Carajás, collected R$4.314 billion in federal mining royalties, making them Brazil’s top recipients.

The contrast with Amazonas, another major mineral frontier that encountered a fully entrenched blockade when it sought to develop its subsoil riches, is stark.

Pará’s success, driven largely by iron ore exports, hints at the Amazon’s broader potential.

One can envision a future in which the Amazon and Brazil exercise full sovereignty over their geography and resources, harnessing them for the benefit of the region’s people and the nation as a whole.

When organized, regulated, monitored by environmental agencies, taxed for the benefit of municipalities, states, and the Union, and conducted with social and environmental responsibility, mining offers a living promise of national and social emancipation—capable of elevating Brazil’s stature in the global economic and geopolitical landscape.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that demand for minerals critical to clean energy will double or quadruple by 2040. These strategic minerals—whether called noble, rare, or critical—are essential for batteries (aluminum, nickel, copper) and renewable infrastructure such as solar panels and wind turbines (copper).

According to the newspaper Valor, Brazil is highlighted in an OECD report citing significant global reserves of nickel, manganese, and rare earths.

Yet, as geologist Roberto Perez Xavier, executive director of the Agency for the Development and Innovation of the Brazilian Mineral Sector (ADIMB), notes: “Brazil still has its mineral potential underexplored, especially for the group of critical minerals.”

There is no doubt that the blockade imposed by foreign-funded NGOs and Brazilian state agencies themselves discourages investment in inventorying the nation’s mineral wealth, particularly in the Amazon. In Brazil, estimating the time required to obtain an environmental license—even for research—is uncertain.

Few venture into the labyrinth of Brazilian environmental legislation without the backing of specialized law firms.The challenge is immense.

Supported by the Amazon, Brazil would be rich and powerful—not another Switzerland, Belgium, or Netherlands on the world stage, but an economic and geopolitical peer to China.

This prospect, undesirable to the northern hemisphere’s great superpower and its Western European allies, may well explain the obstacles to fully incorporating the Amazon into Brazil’s national development project and future.