USAID & THE AMAZON REGION

by Antoine Bachelin Sena.

Summary:

- Historical introduction to key organizations and individuals.

- Public opinion is increasingly aware of international interference against Brazilian development.

- Studies funded by USAID against Brazilian infrastructure.

- USAID feeding the octopus of NGOs and the Ministry of the Environment or the Ministry of NGOs.

- The “Project Democracy” apparatus has been very active in influencing selected brazilian parliamentarians to follow Washington’s economic hegemony program.

- “ABIN” or the Brazilian Intelligence Agency reveals that USAID has configured external interference in the Amazon region and facilitated biopiracy.

- Conclusion with the urgency to put on the agenda the “Bill PL 1659 of 2024” by Federal Deputy Filipe Barros to increase transparency and control over NGOs operating in Brazil with foreign funding.

- Link to the book “Political Amazon: Land Demarcation and Globalist NGOs” and presentation of the author Antoine Bachelin Sena.

Historical Introduction to Key Organizations and Individuals.

We can start when several Brazilian organizations, including indigenous and environmentalist movements, united to form the “Instituto Socioambiental” (ISA). This entity inherited the archives and expertise from the “Centro Ecumênico de Documentação e Informação” (CEDI) and the “Centro de Direitos Indígenas” (NDI).

Indigenous and separatist activism in Brazil began to take shape in 1965 with the creation of the “Centro de Informação de Missões Ecumênicas” (CEI), which evolved in 1974 under the leadership of Anivaldo “Niva” Padilha into the “Centro Ecumênico de Documentação e Informação” (CEDI).

Padilha, supported by the “Conselho de Igrejas”, transformed the CEDI into a convergence center for various religious and theological trends, including “Liberation Theology” and existentialism, which were conducive to organizing insurgent movements.

The CEDI played a key role in supporting figures like Leonardo Boff and others in the Marxist-Christian dialogue, which later influenced guerrilla movements in Central America.

One of the leading names of the “Instituto Socioambiental” (ISA), Márcio Santilli, a philosopher by training, played a crucial role in the formation of the institute. Santilli, having served as a federal deputy in São Paulo and chaired the Indian Commission in the Chamber of Deputies, later engaged in coordinating indigenous efforts at the 1987-1988 National Constituent Assembly before taking over the leadership of “FUNAI, the National Indian Foundation.”

The international connections of Santilli and the “ISA” also include the “International Cocoa Organization (ICCO)”, an intergovernmental organization established in 1973 under the auspices of the United Nations with a contribution of about 1 million US dollars and the Packard Foundation (108,000 US dollars).

The ISA has also been influenced by internationally recognized figures in the fields of environment and indigenous rights.

For example, Barbara Bramble from the “National Wildlife Federation” (NWF), one of the largest American NGOs, played the role of “executive director” at the Altamira meeting, influencing both American and international environmental policy, particularly regarding the financing of foreign projects by the American federal bank.

Stephen Schwartzman from the “Environmental Defense Fund” (EDF) is another notable figure linking the “ISA” to international actors. He contributed to pressuring the “Inter-American Development Bank” to suspend loans for certain Brazilian projects, notably the BR-364 highway.

Schwartzman, with his connections to INESC and other American environmental groups, was also an activist in blocking Brazilian infrastructure projects like “Polonoroeste” and “Carajás”.

Thus, the “ISA”, under the leadership of personalities like Santilli, not only served as an instrumentalist for the environmentalist and indigenous apparatus in Brazil but also wove an international network of influence, linking Brazilian policies to global environmental dynamics.

The Amazon region is a subject of study and action for several influential figures in anthropology, environment, and sustainable development:

- Jason Clay began his engagement in the Amazon as a graduate student in 1972, focusing on rural leagues. After obtaining a doctorate from Cornell and studying at the “London School of Economics”, he worked for “Cultural Survival”, where he tripled the number of associates and quadrupled contributions.

Clay advocated for ethnic nationalism with the aim of fragmenting and weakening the nation-state and was active at the Altamira meeting, influencing environmental policies and indigenous rights.

- Willem Pieter Groeneweld, founder of the “Instituto de Pré-História, Antropologia e Ecologia” in Porto Velho, Rondônia, with support from the Swedish NGO “Friends of the Earth”. He worked as a consultant for mining companies while being supported by “CIDA” for the “Rio-92” conference.

His activities included acting as an influence agent in Acre and collaborating with the Canadian embassy.

- Anthony “Tony” Cross, representative of “Oxfam” in Brazil, was instrumental in turning figures like Chico Mendes into international celebrities for the environmental cause.

He also introduced Mary Helena Allegretti into international ecological circles, influencing Brazilian environmental policies. “Oxfam”, under Cross’s leadership, was linked to separatist movements in Mexico and Sri Lanka, reflecting engagement in socio political struggles. His influence extends beyond Brazilian borders, impacting international politics and global perceptions of Amazon management.

- Carlos Alberto “Beto” Ricardo, an anthropologist with extensive experience in NGOs, co-founder of the “CEDI” and involved in various environmental and indigenous organizations, received the “Goldman Environmental Prize” for his work.

- José Carlos Libânio, also an anthropologist, served as an advisor for several organizations, including the UNDP for sustainable development.

- In October 2002, Jecinaldo Barbosa Cabral, coordinator of “COIAB,” participated in a conference in London, supported by organizations like “Survival International” and “Amnesty International,” to discuss the involvement of indigenous communities in conservation policies.

“COIAB” is closely linked to the “Washington Amazon Alliance,” a coalition of influential environmental and indigenous NGOs.

Existing discussions and events reveal an international geopolitical strategy aimed at influencing Brazilian agrarian policy.

Public opinion is increasingly aware of

international interference against Brazilian development.

The activities of these individuals and other NGOs show a trend of intervening in indigenous and environmental affairs in Brazil with the support of international funding. These interventions have often been criticized for their influence on Brazil’s domestic policies, which conflict with national or local interests, such as land exploitation or the management of natural resources.

Brazilian public opinion is increasingly aware of international interference and internal security issues related to infrastructure development for the benefit of Brazilian citizens.

There is frustration and strong criticism towards these NGOs and associated figures for several reasons: the exploitation of indigenous lands, the influence of foreign aid, and the management of indigenous rights.

For example, one criticism points to the neglect of indigenous communities, suggesting an ineffective or biased indigenous policy.

Another critique highlights that indigenous peoples are more interested in basic services like drinking water and electricity rather than acquiring more land, possibly reflecting dissatisfaction with how indigenous policies are implemented and instrumentalized by NGOs and international interests.

In Brazil, only 6% of wastewater is treated and 40% of the population does not have access to treated water! Indigenous people are isolated by executive decree, without access to electricity or sewage, with no possibility for development, while NGOs and international funding proliferate…

A study presented in 2004 by the coordination of higher studies and engineering research at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (COPPE-UFRJ) revealed that 68% of diseases in the public hospital network were caused by contaminated water, with a monthly cost of 250 million reais just to treat these cases.

Despite the expansion of understanding on this topic, the environmentalist-indigenous movement has reached what might be the peak of its influence in Brazil.

The movement has become an important part of the power structure, directly interfering with public policies and the activities of the most diverse productive sectors, acting, as we will see, as an obstacle to these activities!

Today, estimates indicate there are about 850,000 active NGOs in the country, receiving over 18 billion reais annually in federal subsidies.

What is most concerning in this context is that the federal government does not have a reliable record of the actual services provided by these organizations, where they truly operate, and how they operate.

Studies funded by USAID

against Brazilian infrastructure projects.

The central thesis of the pseudoscientific document “Avança Brasil: The Environmental Costs for the Amazon” was prepared to make it difficult to build roads and other infrastructure in the Cerrado-Amazon region, which was part of the “Avança” program:

- The Cuiabá-Santarém highway (BR-163),

- the section of the Trans-Amazon highway between Marabá and Rurópolis (BR-230),

- the Humaitá-Manaus highway (BR-319)

- and the Manaus-Boa Vista highway (BR-174).

By linearly extrapolating data collected, mainly at the intersection of the Belém-Brasília highway, its authors conclude that these roads would lead to the deforestation of 188,000 square kilometers in the next 25 to 35 years, considering a 50-kilometer strip along the 3,600 kilometers of these road edges.

In other words, if one considers the entire length of the highways and wider side tracks, the deforestation of the “inflammable forest area”, as the authors describe it, would be much greater.

What is explicit in the document is that the Belém-Brasília, Cuiabá-Porto Velho, and PA-150 highways, at the basis of their research, should never have been built because of the “destruction” they caused and could intensify.

And for them, their decisive role in development, integration, and territorial occupation, which could be much greater with paving, matters little.

For them, the Belém-Brasília should still be called “Uncle Sam’s Path”, as it was at the time of its construction.

It’s important to note that the studies were sponsored by the US “Tinker Foundation”, the Swiss “Avina Foundation”, and the “United States Agency for International Development (USAID)”.

In May 2003, the Lula government announced its intention to finance part of the projects in the “Multi-Year Plan (PPA) 2004-2007” for development and to attract the private sector with the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) program.

On the same occasion, representatives from the agricultural sector and the industries of the Manaus Free Trade Zone decided to defend the concession of the BR-163 highway and to finance what was necessary for its paving between the border of Mato Grosso and Pará and the municipality of Miritituba (PA).

The partnership allowed for opening a new route for products from the Manaus Free Trade Zone and agricultural sector production flows from the region through the port of Santarém.

At this event, the Governor of Mato Grosso, Blairo Maggi, informed that the proposal would receive support from President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the Minister of National Integration, Ciro Gomes, and that the BNDES had shown interest in financing the works according to CCNPRESS, “Consórcio BR-163 follows the PPP model with federal government support.”

A few days later, a network of NGOs led by “Friends of the Earth” launched an online portal called “red light”, listing a series of actions presenting a “high risk of social and environmental impact on local communities”.

The obvious aim of this initiative was to intimidate, pressure, and halt progress.

For example, the paving of BR 163 was described as an element that “could generate a new cycle of uncontrolled economic frontier expansion in a key area of the Amazon, causing logging, deforestation, fires, rural exodus, urbanization, and problematic environmental policies!”

Seriously, just for paving!

One way to prevent the development of Northern Brazil is to act against its transportation infrastructure.

The institution is called “Solidarity Center”.

Here, we see a union from the United States, funded by U.S. government funds, along with the CUT, opposing the Tocantins waterway project.

They have the Mississippi waterway and are acting here against the Brazilian waterway.

And they still have the audacity to claim it’s a demand from the “Peoples of the Amazon.” Another attack on the country’s sovereignty.

USAID feeds the octopus of NGOs

and the Ministry of the Environment or the Ministry of NGOs.

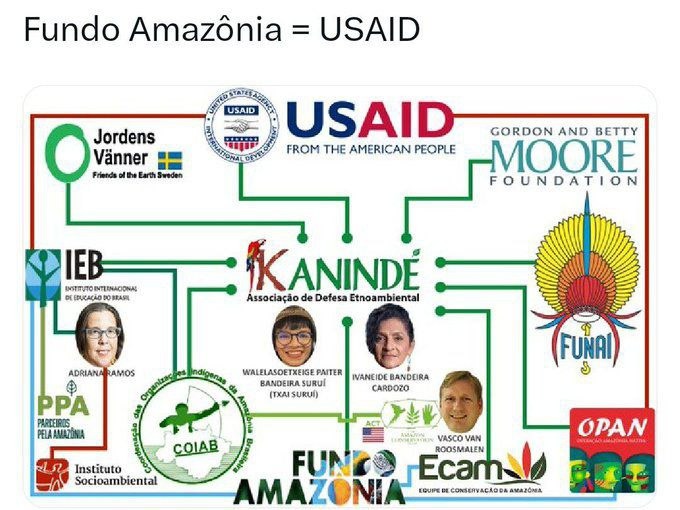

The Amazon Fund is an international fund that finances projects for conservation and sustainable use of the Brazilian Amazon.

USAID (United States Agency for International Development): U.S. government agency.

- Jordens Vänner (Friends of the Earth Sweden): Swedish environmental organization working to promote environmental and social justice. Its participation in the Amazon Fund indicates its financial or technical support for conservation initiatives.

- Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation: U.S. philanthropic foundation that finances projects in science, environmental conservation, and quality of life improvement.

- Kanindé: Ethnoenvironmental Defense Association, focused on defending the rights of indigenous peoples and environmental conservation. It receives financial support from the Amazon Fund for its activities.

- IEB (Instituto Internacional de Educação do Brasil): Organization working in the fields of education, sustainable development, and environmental conservation. It receives funds from the Amazon Fund for its projects.

- FUNAI (Fundação Nacional do Índio): Brazilian government body responsible for the protection and promotion of indigenous peoples’ rights. It participates in the Amazon Fund to support initiatives that benefit indigenous communities.

- COIAB (Coordenação das Organizações Indígenas da Amazônia Brasileira): Entity representing the indigenous peoples of the Brazilian Amazon, working for the defense of their rights and interests. It receives support from the Amazon Fund.

- Instituto Socioambiental: Non-governmental organization working on environmental conservation and the rights of indigenous peoples and traditional communities. It receives funding from the Amazon Fund.

- OPAN (Operação Amazônia Nativa): Organization working on the protection of indigenous rights and environmental conservation in the Amazon. It participates in the Amazon Fund.

- Vasco van Roosmalen Ecamin: Company or organization involved in conservation projects in the Amazon, funded by the Amazon Fund.

In his testimony before the Federal Senate’s Parliamentary Inquiry Commission (CPI) on NGOs, journalist Lorenzo Carrasco, editorial coordinator of the book “Green Mafia: Environmentalism at the Service of World Government,” warned about the growing influence acquired by non-governmental organizations, particularly in defining policies that should be formulated and implemented by the Brazilian national state!

On this occasion, he stated: “It should be noted that the main funding sources for NGOs within the environmentalist and indigenous apparatus are donations from these multinational corporations and oligarchic families founded by oligarchic families from the Northern Hemisphere (Ford, Rockefeller, MacArthur, W. Alton Jones, etc.), as well as official funding bodies from the main G-7 countries.

Among the latter, we highlight USAID (United States), DFID (England), ACDI (Canada), among others.”

Therefore, it is not surprising that the “agenda” of the environmentalist-indigenous apparatus is illuminated by these hegemonic power centers, rather than by the authentic interests of Brazilian national action.

This fact is even recognized by leaders of the Brazilian environmentalist apparatus, like the former president of “Ibama,” Eduardo Martins, who was also a director of “WWF” in Brazil.

In a report published by the magazine “Veja,” he admits: “About 85% of the resources that NGOs maintain in Brazil come from abroad.

With the money comes also the agenda of priorities set for each country. This creates problems. The environmentalist bias of NGOs becomes a fashionable slogan, which has already had symbols like the elephant and now a kind of tree from the mahogany family. Imagine a group of European ecologists meeting and announcing through NGOs that from now on, the new symbol of the fight for forest preservation is the ‘Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST)’ which invades and burns plantations and crops.

The next day, they forget about the forests and never mention them again.”

The same magazine confirmed the great external dependency of Brazilian NGOs, highlighting that 80% of the $700 million they received annually came from foreign donations and, therefore, with geopolitical and geostrategic demands from abroad!

Even due to the difficulty of tracing these money flows (and the lack of voluntary control for money laundering), it can be considered that this volume of resources has multiplied in the same proportion as the will of the sponsors of the environmentalist-indigenous movement, with the aim of sterilizing the development efforts of the target country.

This dependency on external resources has even contaminated official bodies, such as the Ministry of the Environment and Legal Amazon.

According to reports from the “Institute of Socioeconomic Studies (INESC),” an NGO in Brasília linked to the international environmentalist apparatus and specialized in relations with Congress, more than 60% of the budget comes from donations, exceeding 520 million reais.

It cannot be a mere coincidence that the same amount is allocated in the budget, according to the ministry’s warning, under the heading “other third-party or corporate agents.” Thus, it is not surprising that the ministry quickly employed the services of many NGOs to prepare studies and evaluations that, in general, conclude that several infrastructure projects in the country are “environmentally unviable.”

The ministry has become merely an official channel for funds allocated from abroad to NGOs linked to the international environmentalist apparatus!

Thus, it is not surprising that the increasing radicalism with which these entities have started to approach their responsibilities begins to function, in practice, as an official obstacle to any enterprise seeking to open new development areas.

On this occasion, Carrasco suggested stricter control of the NGO apparatus, particularly of environmentalists.

He says: “The collection and registration of funds managed by NGOs and even by some official bodies are essential for the institutional framing of the activities of entities involved in the environment, so that the distortions that have characterized them can be circumvented.”

As expected, this interference has amplified over the years, especially with the arrival of the Lula government.

Although there are NGOs that carry out activities of real public interest, it is necessary to recognize that the structures of “global governance” are committed to fitting Brazil into their hegemonic plans and use these NGOs to control public policies in key strategic sectors.

Among these are environmental policies, indigenous policies, human rights, education, issues related to social reform, and social security policies, agrarian areas, and even some areas of public security, under the guise of so-called “civil security,” where the key is the insidious campaign for civilian disarmament.

The most serious issue is that bodies without any representation gain effective political power through a sophisticated system of international pressures, which have an effective resonance among the main media outlets in the country, with financial links close to the environmentalist-indigenous apparatus and other international circles. In this modern colonialism, the incursions of companies authorized by the metropolis are replaced by “direct actions” of NGOs and well-coordinated propaganda campaigns involving political circles and manipulations of national and foreign public opinion.

In this scenario, NGOs have been transformed into agile and well-funded units of radical political activism. The advance of NGOs has gone so far as to take control of some ministries and government dependencies.

The most scandalous case is that of the Ministry of the Environment, now known as the “Ministry of NGOs,” not only because of the close ties of Minister Marina Silva herself with the global environmental movement, but also because the latter has provided high-level activists to occupy ten of the most important positions in this federal body.

In addition to Marina Silva herself and her chief of staff, Bruno Pagnoccheschi from the “Instituto Sociedade, População e Natureza (ISPN)”, we have:

- Flávio Montiel da Rocha, director of protection in the environmental department of “IBAMA,” who was the coordinator of the political unit of “Greenpeace” and consultant for the “World Wildlife Fund (WWF-Brasil).”

- João Paulo Capobianco, Secretary of Biodiversity and Forests, was the executive director of the “SOS Mata Atlântica Foundation,” as well as the founder and coordinator of the council of the “Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA).”

- Marcelo Marquesini, coordinator of environmental supervision at “IBAMA,” worked for six years at “Greenpeace.”

- Marijane Vieira Lisboa, Secretary of Environmental Quality, also has a long history of work with “Greenpeace,” where she worked, among other positions, for 10 years as executive secretary and coordinator of the campaign “For a Brazil Free of Biotechnology.” She was recently replaced by Ruy de Góes, former coordinator of the “Greenpeace” campaign against the Brazilian nuclear program.

- Tasso Rezende de Azevedo, program director of the Secretary of Biodiversity and Forests, was the executive secretary of the “Institute for Biodiversity and Forests (IMAFLORA).”

- Muriel Saragoussi, director of the “National Council for the Environment (Conama),” comes from the “Vitória Amazônica Foundation (FVA).”

Also holding key positions are:

- Atanagildo Fonseca from the “National Council of Rubber Tappers” in the Secretariat for Coordination of the Amazon;

- Bren Milikan from the “Rondônia NGOs Forum”;

- The Secretary for Sustainable Development and former federal deputy Gilney Viana, sponsored by NGOs. The husband of this Secretary for Sustainable Development, Fábio Vaz de Lima, is the former secretary of the influential “Amazon Working Group (GTA),” a conglomerate of 200 NGOs active in the Amazon.

Vaz’s name appeared in the press in connection with a scandal involving the sale of mahogany (a reddish-brown wood), seized by “IBAMA” and then “resold” to the “Federal Federation of Social and Educational Assistance (FASE)”.

Despite this, he remains a member of the “Amazon Working Group (GTA)” and receives his salary without interference.

In indigenous policy, NGOs dominate, for example, the provision of services to Indians, legally under the guardianship of the Union. NGOs dominate, for example, the provision of services to Indians, a population under the guardianship of the Union.

NGOs and indigenous organizations have been tasked with health and sanitation in tribes. They buy medicines, materials, fuel, and even vehicles for the execution of sanitation improvement and indigenous health programs.

Hundreds of millions have been transferred to 56 organizations:

- For the “Indigenous Council of Roraima (CIR)”, it was 6.7 million reais;

- For the “Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Rio Negro”, 6.35 million reais;

- The “Caiuá Evangelical Society” received 7.2 million reais.

Until recently, before the Ministry of Health regained control over the purchase of medicines, fuel, and equipment through the “National Health Funds (Funasa)”, these functions were utilized by indigenous NGOs linked to sectors of liberation theology and the World Council of Churches, according to “O Globo”!

According to data from the “Integrated Financial Administration System (SIAFI)”, landless settlers’ cooperatives received funds from the “National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA)” to develop agrarian reform projects.

- For the “Central Cooperative of Agrarian Reform of Paraná”, this amounted to 836,600 reais.

The “Project Democracy” apparatus has been very active

in influencing selected brazilian parliamentarians

to follow Washington’s economic hegemony program.

Journalists Silvia Palacios and Lorenzo Carrasco revealed this interference, and the project was denounced at the Congress by Federal Deputy Luiz Alfredo Salomão (PDT-RJ).

On its side, the “IAF” sent financial resources to several NGOs operating in Brazil. The maneuver was uncovered when the Central Bank of Brazil sent information about the transactions.

Among the NGOs cited as beneficiaries of U.S. government funds are “WWF-Brasil” (478,000 R$), “Viva Rio” (458,000 R$), and “Network of Information for the Third Sector” (399,000 R$).

Other donations made by the “IAF” are distributed as follows:

- “Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)”: $143,864;

- “Association brésilienne d’organisations non gouvernementales (ABONG)”: $119,500;

- “Council for Alternative Agriculture Projects (AS-PTA)”: $196,200;

- “Federation of Organs for Social and Educational Assistance (FASE)”: $538,350;

- “Institute of Socioeconomic Studies (INESC)”: $112,012;

- “Institute of Religious Studies (ISER)”: $192,064;

- “Brazilian Institute of Economic and Social Analysis”: $220,500;

- “Center for Life Institute (ICV)”: $297,568;

- “O Boticário Foundation for Nature Protection (FBPN)”: $550,000;

- “Viva Rio”: $314,200.

NGOs operate as intelligence services.

An increasing number of governments around the world have publicly expressed their concerns about the lack of control over NGOs in their countries.

Foreign intelligence services use NGOs to collect information and promote the interests of the core of Washington’s hegemonic forces around the globe.

The absence of legislation and effective state control mechanisms creates fertile ground for intelligence operations under the guise of humanitarian aid and other activities.

The “ABIN” or Brazilian Intelligence Agency reveals that

the “USAID” has configured external interference

in the Amazon region and facilitated biopiracy.

“ABIN” reports that “USAID” is responsible for subcontracting actions of large-scale NGOs, such as the “Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA)”, “World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)”, and the “Institute of Man and Environment of the Amazon (Imazon)”.

Documents from the Brazilian Intelligence Agency sent to the NGOs CPI and consulted suggest that a consortium funded by the American government agency “USAID” might configure an attempt at external interference in the region and even facilitate biopiracy. The commission has opened a new line of investigation. Some actions involve satellite monitoring of roads, traditional communities, and forest typologies.

The Parliamentary Inquiry Commission (CPI) investigating the actions of NGOs in the Amazon has opened a new line of investigation pointing to risks of espionage, biopiracy, and manipulation of traditional communities in the most coveted region of the planet. The documents provided by the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN) to the committee show how third-sector organizations respond to external interests and sometimes conflict with those of the Brazilian government.

In a set of reports reaching 490 pages, ABIN cites international funding as the driving force behind the actions of these NGOs and points to “attempts at external interference” in the most coveted region of the planet.

The Brazilian Intelligence Agency mentions USAID, the U.S. government agency for humanitarian and economic assistance to other countries, as one of the main sources of funding for these activities.

Other international funding sources are also listed, such as foreign private foundations.

In one of the paragraphs, the document states that “these non-governmental organizations seek to influence indigenous organizations and traditional peoples in a direction opposite to the construction of infrastructure projects planned by the Brazilian government”.

According to ABIN’s assessment, this would result in difficulties imposed on infrastructure projects, as well as tension in relations between these communities and Brazilian government agents.

The construction of hydroelectric plants in the Amazon region is mentioned as one of the sensitive points by the report. ABIN indicates that, after the expropriation of areas from the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, there was a decisive action by NGOs to encourage families to settle along the banks of the Contigo River – to, in the future, justify the existence of communities and thus block the start of construction of the Contigo Hydroelectric Plant.

According to ABIN documents, this action has turned into “a model that has become routine in the Amazon region whenever an infrastructure project is considered”.

Brazilian intelligence emphasizes that sometimes relevant actions for local communities and environmental preservation are perceived from NGOs in partnership with public authorities.

However, ABIN notes that “political implications remain, given that the positioning of these organizations – materialized in media campaigns – often conflicts with infrastructure projects in the region”.

The document mentions the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant in Altamira, Pará, which faced strong opposition from segments of international civil society.

Protests with the mobilization of transnational NGOs marked the construction of Belo Monte and the Tapajós hydroelectric complex.

“They formed a ‘pact of forces’ for the launch of a global mobilization for the rights of Indians and against the construction of the UHE (Hydroelectric Plant) Belo Monte and other UHEs in indigenous areas and include:

- claims and demonstrations to multilateral international organizations;

- visits to European NGOs;

- meetings and encounters with national and international indigenous leaders;

- petitions, films, and videos,” the ABIN document continues.

Interference and biopiracy.

Another point highlighted by intelligence concerns the sale of carbon credits.

The ABIN document further speaks of an “attempt at external interference in the elaboration of management plans and the articulation of organizations funded by USAID with the state government and with some indigenous leaders with a view to the possibility of selling carbon credits”.

The report also indicates that certain NGOs sell packages under the guise of tourism to facilitate the entry and activity of foreign researchers in the Amazon.

One of the NGOs mentioned is the Amazon Association operating in the rural community of Xixuaú, Roraima, receiving support from Italian and British entities.

According to ABIN, this action leads to a “risk of unauthorized access to Brazilian genetic heritage”.

The documents condensed in this report were produced between 2002 and 2023.

ABIN acts with the mission to anticipate events and situations that could impact the security of Brazilian society and state.

Since the agency does not have police powers, the reports produced are available to the government for follow-up and to define subsequent actions.

“We are opening a black box,” says the president of the NGOs CPI According to Senator Plínio Valério (PSDB-AM), president of the NGOs CPI in the Senate, the ABIN reports reinforce a line of investigation that the committee was seeking to follow, that of showing who finances the organizations operating in the Amazon.

“What ABIN says, and what we show, is that in addition to saying that these NGOs have international relations, they are funded by large international funds.

That’s what we want: to open the black box and show Brazil how harmful these environmental NGOs are and how they harm Brazil.

They accept money from foreign governments to influence Brazil’s environmental policy, and we are at that stage now, having the names of the NGOs and those who finance them,” reflects the senator. Plínio Valério highlights that the team is using the ABIN reports, but he notes that much of the information contains confidential data – and therefore, even the commission does not have full access to names and locations.

“There are some confidential data and names that they omit. But we use them at this moment to formulate questions and define actions,” he details.

Parallel State.

The international funding of NGOs operating in the Amazon was even mentioned by the former Defense Minister, Aldo Rebelo, during a CPI hearing in July of this year.

At the time, Rebelo mentioned the existence of a “Parallel State” in the Amazon.

Although not part of the NGOs CPI, at the end of October, Deputy Alexandre Ramagem (PL-RJ) requested from the Joint Commission for Control of Intelligence Activities in Congress that ABIN provide all reports produced by the agency on the actions of NGOs over the last ten years.

Ramagem led ABIN during Jair Bolsonaro’s administration. In his request, the deputy spoke of “problems encountered by the third sector” in the country, which, according to him, “in most cases are related to bad faith people who create NGOs to facilitate the receipt of resources (public and private), but do not work in the promised area”.

In addition to the consortium including ISA, among the most active NGOs in the Amazon, ABIN cites:

- The Amazon Conservation Team (Ecam),

- World Wide Foundation (WWF-Brasil),

- The Nature Conservancy Amazon Program (TNC),

- Conservation International (CI),

- Institute for Research and Training in Indigenous Education (Iepé),

- Rainforest Foundation,

- Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI),

- New Tribes Mission of Brazil (MNTB),

- of Waipi Indigenous Peoples of the Amapari Triangle (Apiwata),

- Wajapi Villages Council (Apina),

- Association of Indigenous Peoples of Tumucumaque (Apitu),

- Association of Indigenous Peoples of Oiapoque (Apio),

- Amazon Work Network (GTA).

These NGOs act autonomously, jointly, or through partnerships with public bodies related to environmental and indigenous issues in Brazil.

ON ABIN’S LIST Main funders of NGOs in the Amazon region:

- Foreign private foundations:

- Blue Moon Foundation;

- Green Grant Fund;

- Charles Stewart Mott Foundation;

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation;

- Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation;

- Clinton Global Initiative.

- Corporation-linked foundations:

- Boticário;

- Coca-Cola,

- Ford;

- Itaú;

- HSBC;

- Natura;

- Nokia;

- Panasonic;

- Pfizer;

- Rockefeller;

- Shell;

- Walmart.

- State international development agencies:

- United States (USAID);

- Germany (GTZ);

- Japan (JICA).

- International organizations:

- UN;

- World Bank;

- European Union.

- Embassies:

- United Kingdom,

- Norway,

- Sweden,

- Netherlands,

- Switzerland,

- Germany

(Source: Intelligence Report no. 0391/82260/ABIN/GSIPR/Oct 15, 2012)

Bill Proposal (PL 1659 of 2024) by Federal Deputy

Filipe Barros to increase transparency and control

over NGOs operating in Brazil with foreign funding.

Federal Deputy Filipe Barros from Paraná has introduced a bill (PL 1659/2024) aimed at restricting the activities of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Brazil, particularly those receiving foreign funding.

Objective of the Project:

The main goal is to enhance transparency and control over NGOs operating in Brazil with external funding. The project seeks to limit foreign interference in the country’s internal policies, ensuring that NGOs operate in line with national interests.

Main Provisions:

- Financial Transparency: NGOs receiving funds from foreign sources must submit a semiannual report on the funds received, specifying their origin and use. This information must be published online.

- National Registry: The project proposes the creation of a National Register of Non-Governmental Organizations (CNO), managed by the Ministry of Justice, where all NGOs receiving foreign funds must register.

- Restrictions on Foreign Funding: There is a clear intention to limit or more strictly control foreign funding for NGOs, ensuring there is no undue interference in Brazil’s internal affairs.

Justification and Context:

Filipe Barros argues that this measure is necessary to guarantee national sovereignty, ensuring that all actions of NGOs within the country are transparent and aligned with Brazilian interests. He mentions concerns about the influence of international organizations, particularly in sensitive areas like politics and the environment.

Legislative Procedures:

The project is still under review in the Chamber of Deputies, subject to revision by the Constitution, Justice, and Citizenship Commission (CCJ).

This project reflects an increased trend of control over non-governmental organizations as a safeguard for national sovereignty.

Since 2001, when the Brazilian Federal Senate established the Parliamentary Inquiry Commission on NGOs, means have been explored to establish control over financial resources received by NGOs, and the topic has received special attention.

The press has alerted the public with detailed reports on the lack of control in the NGO sector. In one of them, published in the newspaper “O Globo” on May 3, 2004, titled “The Power of NGOs in the Government,” journalist Catia Seabra exposes the substantial resources accumulated by the NGO sector.

The Senate has already approved in 2004 a substitute by Senator César Borges (PFL-BA), which modified an original text by Senator Ivofarildo Cavalcanti (PPS-RR), defining this institutional structure.

The proposal requires NGOs to report their resources annually in a public registry. Indeed, the issue of public money transfers to NGOs has raised concerns in official circles.

For example, the Attorney General of the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), Lucas Furtado, complained about the lack of objective criteria for selecting NGOs that receive public money: “When you go to check different points for an agreement, there are no criteria established by a procedure to follow.

And the big problem is that, in recent years, the volume of resources transferred to NGOs has increased. To register in the public registry, an NGO must explain to the Court of Accounts the actions it will carry out and “the names and qualifications of its administrators and representatives as well as any other information deemed relevant for the evaluation of its objectives.”

Moreover, the activities of foreign companies on national territory now require prior authorization from the Justice Forum.

Similarly, personalities from scientific, intellectual, and business communities have not ceased to express their strong concerns regarding NGO activities.

For instance, geographer Aziz Ab’Saber from the “Institute for Advanced Studies of the University of São Paulo (USP)” considers “absurd” the launch of public-private partnerships by the Ministry of the Environment for the management of preservation areas: “They want to lease national forests to foreign NGOs for 30, 60 years.

The areas become farms, and the day the country disagrees, the issue will be taken to an international court.

In fact, it’s the internationalization of the surroundings of national forests. In 60 years, we will see what remains, if anything remains!”

The need to oversee the issue of NGOs, particularly those working with public funds, has already been discussed at the Superior Council of the Public Prosecutor’s Office of the State of São Paulo, and bills are under review in the National Congress to establish a minimum level of control over their activities.

Some cases are so serious that the federal government decided to create an inter-ministerial working group (GTI) specifically to discuss the issue and propose a solution. Cezar Alvarez, General Under-Secretary of the Presidency of the Republic, was appointed as the rapporteur for the GTI.

In an interview with “Jornal do Commercio”, Alvarez stated that modernizing concepts and practices is one of the first steps to establishing a new relationship between the State and NGOs and creating effective mechanisms to control the expenditure of public funds.

In addition to filling outdated legislative gaps, it is necessary to eliminate terms like philanthropy and charity from public-private partnership procedures and address the enormous legal loopholes.

It is necessary to equip the government with instruments for a quality partnership.

At the same time, the government has responsibilities regarding the qualification of this partnership, transparency of accounts, and how it will be renewed.

Similarly, the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) has revealed several irregularities in the transfer of public money to NGOs.

One factor is the absence of objective legislative criteria for selecting NGOs to receive public money, which needs to be corrected to compel them to account to society.

Link to the book “Political Amazon:

Land Demarcation and Globalist NGOs”.

Buy the book here : https://a.co/d/b9QDb79